In her book Shigeko! Hiroshima kara umi wo watatte (Shigeko! A Girl from Hiroshima Crosses the Ocean), Seiko Suga chronicles the life of Shigeko Sasamori, a woman who was badly scarred in the atomic bombing, received reconstructive surgery in Tokyo and the U.S., and later permanently moved to the latter. The nonfiction book, published in 2010, is framed by Seiko meeting with Shigeko in Hiroshima to learn about her life; the chapters then switch to Seiko narrating Shigeko’s experiences in third person. Although Shigeko! is unavailable in English, the Japanese, targeted at children in late elementary school, is easy enough to understand without perfect knowledge of the language.

In her book Shigeko! Hiroshima kara umi wo watatte (Shigeko! A Girl from Hiroshima Crosses the Ocean), Seiko Suga chronicles the life of Shigeko Sasamori, a woman who was badly scarred in the atomic bombing, received reconstructive surgery in Tokyo and the U.S., and later permanently moved to the latter. The nonfiction book, published in 2010, is framed by Seiko meeting with Shigeko in Hiroshima to learn about her life; the chapters then switch to Seiko narrating Shigeko’s experiences in third person. Although Shigeko! is unavailable in English, the Japanese, targeted at children in late elementary school, is easy enough to understand without perfect knowledge of the language.

Shigeko’s story begins on August 6, 1945, when she was 13 years old. After being exposed to and horribly burned by the atomic bomb near Tsurumi Bridge, Shigeko managed to walk to what is now Danbara Elementary School, where she laid semi-conscious for four days without receiving medial attention, food, or water. She continuously mumbled her name and address, and finally someone told Shigeko’s family where she was. After bringing her home, Shigeko’s family nursed her back from the brink of death, but she still had severe keloid scars on her face, neck, and hands, the latter of which would give her a lifelong slight handicap.

After meeting Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto at Nagarekawa Methodist Church, Shigeko joined a group of young women all scarred by the bomb. Some of them traveled to Tokyo to receive reconstructive surgery; it was then that the term “Atomic Bomb Maidens” became widely publicized in Japan. Through Reverend Tanimoto’s introduction, Shigeko met journalist and writer Norman Cousins, who was visiting Hiroshima with his wife. Cousins raised money for 25 young women from Hiroshima, including Shigeko, to undergo more surgery New York City in 1955. Inspired by both her time in the U.S. and in hospitals, Shigeko decided to return to the States in 1958 to study nursing. She became Cousins’ adopted daughter.

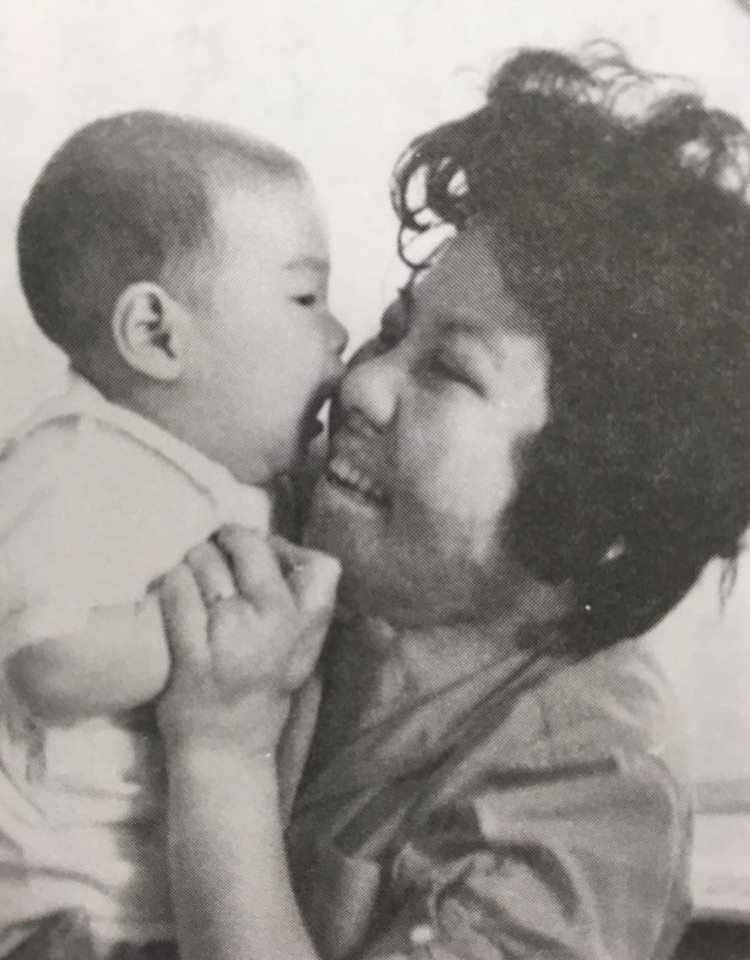

The book then follows Shigeko as she works hard to master English, become a nurse’s aide, help difficult but ultimately gracious patients, and raise her son. Over the years, Shigeko began to do more and more public speaking. After retiring from nursing, she visited schools, universities, and other functions to share her experience of the atomic bombing and advocate for peace. Shigeko also visited Chernobyl to speak with people affected by the nuclear disaster there.

The author closes the story with two examples of Shigeko speaking to students in the U.S., one at an elementary school and the other at Winona State University, from which Shigeko received an Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters in 2009. In her talks, Shigeko spoke about hating and fearing war itself rather than the country that dropped the atomic bomb, about young people’s potential to create a peaceful world, and about the necessity of living one’s life with courage, action, and love.

Shigeko! rewrites “Atomic Bomb Maidens” as “Hiroshima Girls” in more than just name. While undergoing surgery in Tokyo and before their departure to the U.S., Japanese media referred to the group by the former moniker. However, Shigeko and the other young women didn’t much like that phrase — “As if there was nothing more to our lives than the atomic bomb.” Americans often called Shigeko and the others “Hiroshima Girls” instead, which made Shigeko feel more accepted as a person and free in her identity. The bombing of Hiroshima, the people she met, and her experiences in the U.S. all shaped Shigeko’s life, and all are given due weight in Shigeko!

Despite the scope of its story and open view of identity, Shigeko! sometimes lacks complexity. Perhaps simplicity is just a characteristic of children’s literature, but it occasionally feels like something is being left out of the book. Embracing more emotional and social complexity could, in turn, develop readers’ own nuanced understanding of the people and events the story describes.