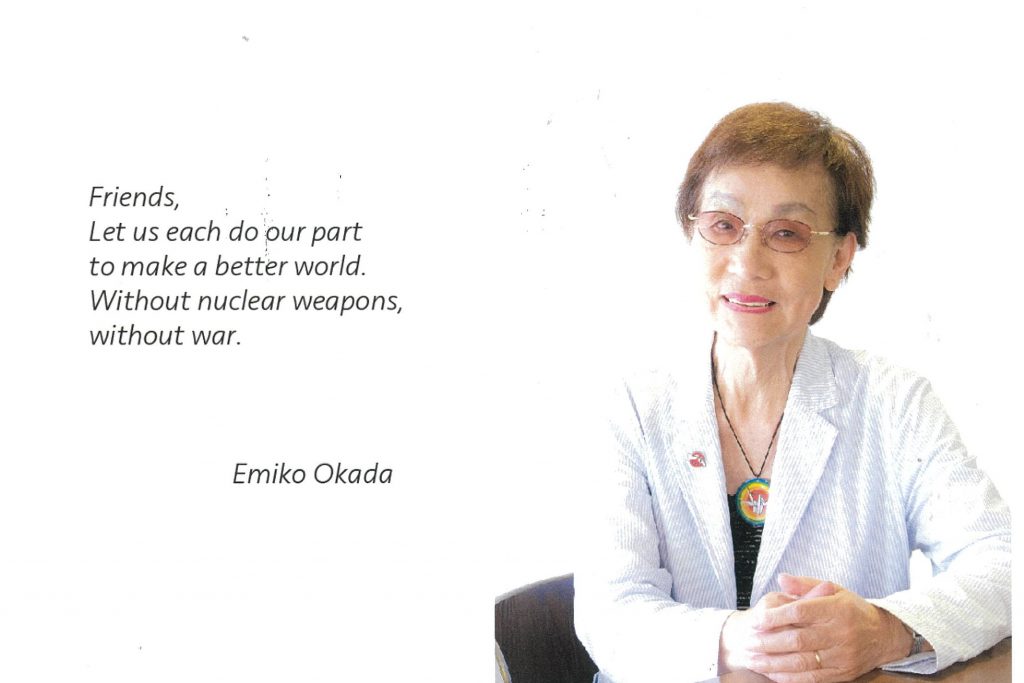

This is the fourth and final part of a series in which we have been uploading the English translation of an interview with Emiko Okada, a survivor of the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima. Her whole story will be told in parts, detailing her early life before the war, her experience in the bombing and its aftermath, her life in the decades following the bombing, and her activism in recent years, in posts over the next few weeks. The interview was conducted in Japanese and has been translated so that her story can be spread around the world, to encourage people to think more deeply about peace and the role of nuclear weapons in the world today. The interview was spoken and has been translated as is, so read it as if somebody was talking to you.

Part one, in which Okada-san speaks of her pre-war life and experience in the bombing, can be accessed here.

Part two, in which Okada-san speaks of her life and struggles following the bombing, can be accessed here.

Part three, in which Okada-san speaks of her activism and peace-building work, can be accessed here.

For Peace

There’s a way to have your thoughts known

Unlike most people, I haven’t studied much and don’t have a lot of information around me. When they held the G8 at Lake Toya in Hokkaido, I sent them a letter. Privately, telling them I was a hibakusha. Asking them, if they had come all the way to Hokkaido, they should visit Hiroshima as well. In America’s case, I sent it directly to the White House. I never imagined that I’d actually get a reply.

Everyone laughed when I told them that I’d sent the letters. They told me, “You know they’ve just thrown it straight in the bin.” Without actually getting to the leaders, one of their assistants would have seen it, scanned it and decided it didn’t need to be delivered, then thrown it out. I thought so too.

Then, I received a reply from the White House. Direct from President Bush. I was so surprised. I got replies from the UK, France and Germany as well. Germany sent me replies in both English and German. Telling me that they’re worried about nuclear weapons too. I was shocked.

They all thanked me for my invitation to visit Hiroshima, but said that the schedule didn’t allow time to visit Hiroshima. They were all simple replies, ended with each countries’ foreign ministers’ signature.

Nobody thought that they would come, no one even thought that they’d reply to my letters, so I was shocked, but happy that they had spent the time reading them. During those few seconds at least, people in all of those countries were thinking about Hiroshima. I think that makes it well worth it.

In 2016, they announced that there would be a summit in Japan, and so I wrote letters again. So I had a letter translated into English, and sent it off to the White House. On a postcard, I simply wrote, please do visit Hiroshima in 2016. There’s going to be a summit, the Ise-Shima G7 summit, so I thought that it was a good chance.

Even if President Obama wanted to come, with the world the way it is these days, there’s not really any opportunities to do so. Given the timing, and the fact that he’d already be here for the G7 meeting, I thought it was a great opportunity. I also asked for him to bring along the other G7 leaders.

My discussions with Clifton Truman Daniel

I’ve been to the US a total of four times. Last time I went to the midwest US, former President Truman’s grandson Clifton Daniel came to meet me.

I never got to meet former President Truman directly, but Barbara organised for other hibakusha, such as Morishita-sensei and Seiko-san to have a meeting with him. Of course, this was a long time ago. On my world pilgrimage, he met me at the Truman presidential library. Of course, I didn’t get an apology. He of course couldn’t say “Sorry”, from their perspective at the time, they had a grudge, a hatred that justified it somehow.

Morishita-sensei doesn’t really show his true emotions. People talk about “A-bombed girls”, but no-one gives time to the “A-bombed boys”. Morishita-sensei is missing an ear, he lost it in the bombing. He’s had countless surgeries to try and restore a normal skin tone, but he’s always bright red. He’s not the type to be able to talk about his story in front of big crowds of people, so he’s kept it bottled up inside forever. His mother died, and though he had his father, they were both lonely, sad and feeling empty. He was one of many impressionable 12-13-year-olds who were hit by the bomb. Nobody would take them in. They had disabilities and injuries, their families were dead or dying. I think he really found his feelings for the first time when he wrote them in poems, by writing them for the first time, he was able to truly understand them.

I don’t know about President Truman’s generation, but his grandson must have had a lot of courage to go all the way to Hiroshima. Even though I’m calling him Truman’s grandson, Clifton himself is in his 60s. Going all that way at that age takes courage. I think it’s like if I went to Korea or China now, I’d go feeling sombre, as if I had responsibility. I told them, if you want to hear my testimony, I’d be happy to give it.

We gave our testimony to them in a room at the Aster Plaza in Kakomachi. There were a few hibakusha giving their testimony, and there were so many different people from the media, all very interested in what we were saying. They were wondering if we would get an apology, so I teased them saying “You’d like that wouldn’t you? It makes for better news!” (laughs) There were so many reporters from many different newspaper companies and tv channels.

When we were giving our testimony, he got misty-eyed, nodded along and listened carefully, I felt that he was a very respectful person. He didn’t apologise afterwards, but he expressed his very sincere gratitude to us for our testimony. He then told us that he would spread the word of Hiroshima to young people in America and around the world.

I took him the seeds of a parasol tree, the descendants of a tree which survived the atomic bombing, and gave him them as a present. The tree was supposed to have died, but it pushed through, grew new leaves and now there are second and third generation trees descended from it. I gave it to him as thanks for coming to Hiroshima as the grandson of Truman.

I also gave him a photobook made by Steven Leeper (of the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation). After he went back to America, I saw him on the news travelling around America and telling people about Hiroshima. I’m grateful to have met him, he is a very sincere man.

My job was finished when I gave my testimony, but then that night I got a call from Morishita-sensei. He told me, “I know that I said I didn’t want to meet Truman’s grandson, but actually, I’ve just met with him.” “Really?!” I said, then he told me “Yes, we shut out all of the media apart from Tashiro-san from the Chugoku Shinbun and I met with him alone.”

Of course, he spoke of how so many impressionable 12-13-year-old children were hurt by the bomb, they lost their parents and he, when he was just a boy, had his face and ears crushed and catastrophic burns on most of his body. He thought of suicide many many times. Even so, when he decided to reintegrate into society, he began to write all of his feelings in poems. He’s a poet, Morishita-sensei. When he was studying poetry, he decided that he had to learn calligraphy as well, and so he went to China many times to brush up on his skills. In that, he found his calling and became a calligraphy teacher.

He got his qualification to teach, but when the time came to actually do it, he was very troubled. He was terrified of actually being in the position in front of so many people, having to teach them. He was so scared, that when he first headed off to be the calligraphy teacher at Hatsukaichi High School, he couldn’t make it to the classroom and there were many times when he fled home in fear.

He was talking about the reason he didn’t want to meet Clifton after having met President Truman in the past.

He even wrote about it in his New Years’ Card. “Clifton wanted to talk to me on the phone, he called after that.”

I met him again after that. I think it was last year, it wasn’t a public visit, but Clifton came with his son. Then we met in Missouri as well. Clifton lives in Chicago, but he went all the way to Missouri to meet with me. He planted the tree I gave him in the garden of the Truman Presidential Library.

I don’t want to hear it. – “What for?”

I think that my late son is looking down, encouraging and protecting me. The things I’m doing these days, I can’t do alone. I have the help and support of so many people. I’ve had my detractors over the years, had many hurtful things said to me.

“Okada-san, why would you do that?”, “Will anything good really come of telling your story?”, “What for?”.

Those sorts of things were especially common when I was doing the survey on landmines. There was some sort of election at the time, I think it was an upper house election I took it to the Electoral Commission office, and everyone signed it for us. Then some asked us, “what are you doing that for?” Isn’t that ridiculous? Those who are involved in politics asking, “What are you doing that for?” When they’re the ones who need to start working.

I thought it was strange, and I couldn’t keep quiet. Looking back, I think that they said it for me, I’ve tried to take it as a positive thing. Everybody told me, “if no positive will come of it, why don’t you stop?”, so I’m making it into a positive. Of course, everybody thinks in terms of the positives and negatives from anything, logically rather than emotionally.

Even the International Hibakusha Appeal (a petition) going around at the moment is like that.

Since President Obama came to Hiroshima, the number of people from around the world coming to visit has gone up exponentially. In the Peace Park, foreigners far outnumber Japanese people these days. Every single day there’s a long line at the entrance to the Peace Museum. I think everybody is seeking peace when they come to visit Hiroshima.

So when those people come, I go and welcome them all to the city and show them the petitions we have, and have them read it. Foreigners are much clearer about what they think, whether they agree or not. If they want to, they sign right away. But whenever I ask Japanese people, they always ask countless questions. “Did you write this?”, “What is that for?”, “Where are you sending it to?”, “Just how long are you doing this for?” I’ve come to see that that’s just how Japanese people are.

All these foreigners from all around the world came to Hiroshima, seeking peace, so I received a lot of signatures in the Peace Park. Then one day, one of the city workers forced me out. I asked why, “Why is it forbidden to circulate a petition which calls for peace, here in one of the world’s biggest symbols for peace?”, and all they could say to me was, “That’s the rule.”

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons

The folks at ICAN are young, so I had high hopes that they would be working for the eradication of nuclear weapons and more widely for world peace when I met with them for the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony. But I did have a few words to say to Kawasaki-san (one of the vital members of the Peace Boat charity). 20-30 hibakusha were going from Hiroshima to attend the Nobel Peace Prize awarding ceremony, but they wouldn’t let us into the building.

If we were just going to watch a video of the ceremony, what did we go all the way there for? I wondered if hibakusha going was actually a main concern for them. The mayor invited us, that’s fine, but would it not be better if some people who had actually experienced the devastation caused by nuclear weapons gave their peace, and the whole thing didn’t just finish with someone simply saying, “for world peace”.

Around 20 of us went, I was encouraged to by Tanaka-san. We sent off our documentation together. “You just won’t be allowed inside.” “You’ll have to watch on a TV. The only ones allowed inside are the mayor, Kawasaki-san and Setsuko Thurlow (a Toronto-based hibakusha very involved in the anti-nuclear movement).

In 2015, I attended the ceremony as part of the 70th anniversary of the bombing. I couldn’t give a speech, but the atmosphere inside was incredible and being able to meet with the people inside was fantastic. I thought if I can’t do that again, why would I go?

High hopes for the young today

At the moment, I tell my story about three times a week. Generally I do it at the Peace Museum, but there are times that I’ll give it at other places.

I’m doing it less than I used to. Now that the city is seeking people to carry on the storytelling, I’m helping them get ready for that. They’re even starting programs to dispatch storytellers across the country as well. Even if they just need to sit and talk, most hibakusha are getting on in age, and so it’s difficult for them to go very far from home. It’s especially hard for them if anything happens wherever they might go.

I can’t move very much, and I don’t have much energy left to leave Hiroshima. I told Steven Leeper this too, when Mayor Akiba gave me an appreciation certificate, he asked me to go somewhere as a hibakusha, and it was just as my passport had expired. When I told him that it had just expired, he told me to get a 10-year passport. I think it’ll be my last passport. My voice still works, though.

It is my life after all, it’s undeniable truth. There are many things I want to forget, but you can’t. I wish there was a memory eraser sometimes.

Though I can’t do anything anymore, I want to give my strength to the next generation of storytellers to ensure that they can do well into the future.

Hiroshima is a symbol of peace, it’s a light of hope in the world.

I don’t want the story of Hiroshima to simply be confined to Hiroshima. I want it to be spread worldwide. I hope young people don’t just gain knowledge of peace, but actually take concrete actions towards achieving it. Not just being nice, but studying hard, smiling and warmly communicating with other people.

There may be setbacks along the way, people have to rest sometimes, but the story of Hiroshima must be spread across the world. It hurts me whenever I see kids crying in warzones on the news. I want to help, but there’s nothing I can do to help them. It hearts my heart deeply. It was very hard watching the disastrous earthquake in the Tohoku region in 2011 too. It’s already eight years since then. All those people have suffered incredible pain, anxiety and been traumatised. They don’t want to remember it. The younger they were at the time, the bigger the trauma was inflicted on them.

From here on, I need to rely on the younger generation to spread the word for me. I also need the help of the media.

I can speak to many children on their school trips, even hundreds at a time, but when the media writes about it, the potential audience goes worldwide. So articles, any reporting, on the internet and such, is greatly helpful. The Hiroshima Peace Media Centre is currently broadcasting new information all the time in both Japanese and English. 10s, 100s of thousands of people are now hearing about Hiroshima. I’ve asked them to all report the true facts. What I and the other hibakusha experienced.

NHK is broadcasting stories about hibakusha internationally these days. Like, television stations from Hawaii called and wanted to talk to Yuuki after her speech at the UN. I heard from Clifton that he had seen my testimony being televised in a teahouse in Thailand. He was surprised, I was speaking English in the program, but that was just NHK dubbing over the top of me (laughs) As soon as he saw it he called to tell me. NHK are doing good work.

I don’t want people to just repeat what they read, I want them to actually say how they feel. Nowadays, you can use your phone and in seconds, you’re broadcasting to the world. I really want people to use that and speak to the world. I want people to remember their real human warmth and share that with the world. By doing that, peace can be achieved.

This concludes our interview with Okada-san. We are working to bring the story of other survivors in the coming weeks and months, so please stay tuned.

English translation by Liam Walsh.