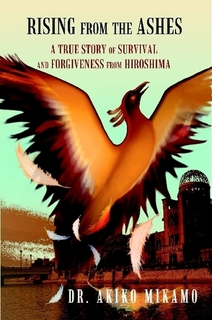

Doctor Akiko Mikamo was born in Hiroshima in 1961, the daughter of two atomic-bomb-survivors. Her book, Rising from the Ashes: A True Story of Survival and Forgiveness from Hiroshima, is a moving account of one family’s experience of the atomic bomb, the suffering, death and destruction it wrought, but it also tells of the resilience and determination to start new lives and ultimately to forgive and move on.

Doctor Akiko Mikamo was born in Hiroshima in 1961, the daughter of two atomic-bomb-survivors. Her book, Rising from the Ashes: A True Story of Survival and Forgiveness from Hiroshima, is a moving account of one family’s experience of the atomic bomb, the suffering, death and destruction it wrought, but it also tells of the resilience and determination to start new lives and ultimately to forgive and move on.

The story is narrated by Doctor Mikamo’s father, Shinji Mikamo, in the first person singular, which informs the account with a dramatic sense of immediacy.

The A-Bombing of Hiroshima

Doctor Mikamo’s future parents were both teenagers at the time of the bombing and both were badly injured by the blast.

Her mother, Miyoko, was working in the Postal Savings Center, just 700 metres from the epicenter, when the bomb exploded. She dived under her desk and was protected from the intense heat by the building, but sustained deep cuts in her back and shoulder from shards of flying glass.

Doctor Mikamo’s father, Shinji, was pulling tiles from the roof of family home in Kamiyanagi-cho, near Sakae Bridge, to prepare it for enforced demolition, a measure that was supposed to prevent the spread of firestorms should Hiroshima be an air-raid target as many other cities on the Japanese mainland had been. The house was about 1,500 metres from the epicentre and when the atom bomb exploded Shinji suffered severe burns all down the right side of his body. He was pulled out of the ruins of the house by his father, Fukuichi Mikamo.

Fukuichi Mikamo

It quickly becomes evident that Fukuichi Mikamo is the true hero of the story. A kind, resourceful man, “forward thinking, practical and rational,” with a sharp sense of humour who, the narrator observes, was possibly the only atomic bomb victim to “laugh sarcastically” that at least the Americans had saved him the arduous job of dismantling his house.

In the immediate aftermath of the bombing it is Fukuichi who forces Shinji to keep going in spite of the intense pain of his burns and injuries. They head east, over Sakae bridge and seek shelter in Toshogu Shrine. The next day Fukuichi insists that they must return to their home rather than wait for death to overtake them. They are repulsed by two heartless young soldiers. Every step in sheer agony, stepping with burnt feet on the dead and dying, or on rubble, splintered shards of wood and other debris, the scorching August sun playing on their burnt and exposed flesh.

Nevertheless, Fukuichi drives his son on until they reach their home. There, they are aided by the kindness of some neighbours, who give them each a bowl of miso soup – their first victuals in two days. They are eventually rescued from the city by a friend of Shinji’s who went to their house in search of them.

Gunzoku

Shinji, as a skilled civilian employee of the army, has the status and privilges of a gunzoku – one who “belongs to the military” – and is taken by the army to a military hospital on one of the islands off the south coast of Hiroshima. Shinji’s father, who is not a gunzoku, is not allowed to accompany him and he never sees his father again.

The harrowing story of Shinji’s survival, his intense sufferiing in hospital, his eventual discharge, also include many intriguing details which are mentioned in passing and add greatly to the interest of the book. For example, that able-bodied adult residents of Hiroshima were not allowed to leave the city without a permit during the war; that when the war was over, and Shinji asked one solder if Japan had won or lost, he replied that he was not sure…

After he is discharged from hospital, Shinji must find a way to make a living. He encounters both meanness and generosity in his struggle to survive. As the only one of his immediate family to have survived, he is reduced to the status of a “street rat”.

Yakuza

He observes that, with the loosening of government regulation, black markets flourished, prices soared and criminal gangs, whose activities had been severely curtailed during the military dictatorship, established themselves once again in the post-war era. The yakuza offered many young men in desperate circumstances an alluring way out of poverty. (For a flavour of Hiroshima’s criminal underworld in the immediate post-war era, see the film series Battles Without Honor and Humanity [仁義なき戦い Jingi Naki Tatakai].)

At the same time, legitimate businesses also began to appear, such as Daichi Sangyo, an electronics company. While one of Shinji’s friends chose the path of the yakuza, Shinji himself dedicated himself to his work as a radio technician, working in a small room in his in-laws’ house.

As Hiroshima emerged from devastation, the city was designated by the Japanese government in 1949 as an International Peace Memorial City, a policy which Shinji, and his daughter wholeheartedly endorsed.

Empathy

The last section of the book before the Afterword contains the most powerful lesson for the author and ultimately for us, the readers. It is a lesson which Doctor Mikami’s father, Shinji, learnt from his own father, Fukuichi, which is the importance of empathy.

In the Afterword, the author writes that we, as human beings, have a choice to “react” (I would prefer to use the word “respond” in this context) to negative experiences with compassion and forgiveness and to see how the other side views things. Her comments here echo those of Viktor Frankl, the German Jewish survivor of Auschwitz, who wrote, in Man’s Search for Meaning, that,

“Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

For Doctor Mikami, the appropriate response is the “surprisingly powerful and liberating” one of empathy because with empathy “you allow yourself room and energy to grow and heal”.

For the author, the very fact that she is alive today seems somewhat miraculous, and her life is informed by a deep sense of purpose, which is to convey the message that yesterday’s worst enemies can be today’s best friends.

As we observe the current civil war in Syria, that may seem unlikely, but Doctor Akiko Mikami, who lives and works in San Diego, is herself a living testimony to the realism of such a belief. In 2011, following the devastating earthquake, tsunami and ensuing nuclear disaster that struck Japan, the USA launched “Operation Tomodachi” – “the single largest humanitarian relief effort in American history”.