The fourth installment of my translations from Yūko Ishida’s Meeting Hiroshima’s Trees is about the ginkgo located in the Anrakuji temple grounds. This is a long excerpt, so please click “continue reading” to read on.

* * *

The Former Chief Priest of Anrakuji: Kōji Toyooka-san’s Story

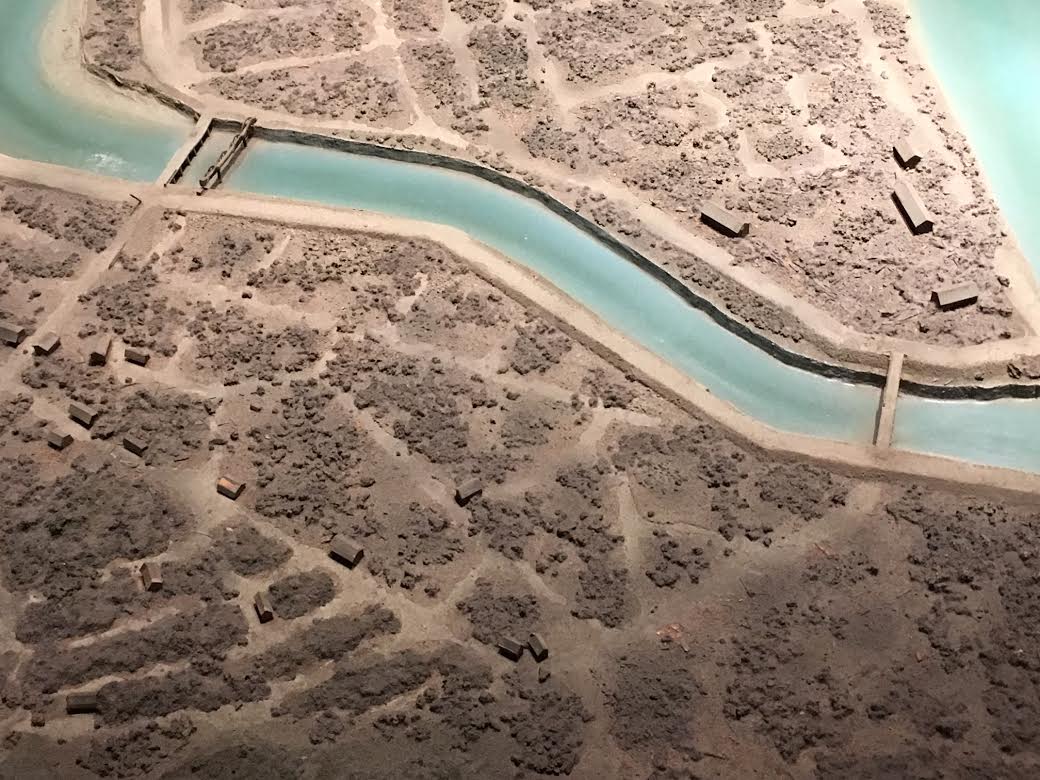

I wanted to hear more from people with knowledge of the bombing, so one day in June of 2014 I inquired at Anrakuji, which is home to the oldest ginkgo in the city. Anrakuji, situated 2.2 kilometers to the northeast of the hypocenter in the Ushita neighborhood, near where Kanda Bridge spans the Kyōbashi River, is an ancient temple with almost 500 years of history. The large ginkgo next to the temple gate is quite tall and can be spotted even from a distance. With its wide and elegant trunk, this tree is a symbol of Ushita.

The first time I saw the ginkgo’s thick branch passing through the roof of the temple gate, I admiringly exclaimed, “Woah, amazing!” Trees growing in cities have their branches cut if they get in the way of electrical lines or buildings. It’s thought that hurting the trees in order to prioritize people can’t be helped. However, this ginkgo is treated with great care. The carpenter designed a magnificent gate, and the tree is clearly growing unimpeded. The branches, growing long and round, were in full, verdant leaf.

That day, I joined third-year elementary school students from Hiroshima City to hear former Chief Priest Kōji Toyooka-san’s personal story of the bombing.

Toyooka-san, wearing the black robes of a Buddhist priest, met us. His expression and figure seemed kind, giving the impression that he was part of the calm atmosphere of Anrakuji itself.

After waiting a little while, we heard children’s energetic voices coming from the street. The ginkgo was probably also happily welcoming its small, lively guests. About 70 kids entered the main hall, sat politely, and quietly waited for Toyooka-san’s story.

Kōji Toyooka-san

Born 1930. Fifteen years old at the time of the bombing (a fourth-year middle school student in the old system).

Location at the time of the bombing: Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Kanon Factory, Minamikanonmachi (4 kilometers from the hypocenter)

・ ・ ・

Everyone, thank you for coming today. When the atomic bomb was dropped in 1945, this hall was thrown into complete disarray. The walls were blown off, the roof completely fell in, and the inside of the building was totally destroyed; only the pillars remained. If you look closely, you can see that the pillars still slant. All the pillars incline the same way because of the blast. In this way, traces of the bomb are still left on this hall.

I was 15 years old and a fourth-year middle school student in 1945. Back then middle school had five years. At that time, middle school students didn’t study, they worked in factories making tools for the soldiers or went to the countryside to help farmers plant and harvest rice.

August 6 had beautiful weather, without a cloud in the sky. I had been mobilized to work at the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries factory that faces Hiroshima Bay. At 8 a.m. I had just begun my work of cutting iron planks.

I was working hard during the instant when the atomic bomb was dropped and don’t remember the moment clearly. I didn’t think anything other than “The sun’s come out from behind a cloud,” and “Huh, it was so bright. I wonder what that was,” but then dust burst in from outside, and it became impossible to stay where I was. I crept through the cloud of dust and jumped out through a window. The factory was large and built well with iron pillars, so it held up even under the atomic bomb. There also wasn’t much damage because it was four kilometers from the hypocenter.

Once I got outside and looked toward the center of Hiroshima City, I saw the white smoke of the terrible mushroom cloud continuously rising. “Whaa — what’s that?” everyone asked as they watched in shock. The white smoke turned pink as it rose. As we exchanged words like, “That’s what smoke from fire looks like. A huge bomb must have been dropped,” and “How strange,” this time we saw the smoke turn black as it continued to billow out.

Eventually, the person in charge of the factory said, “Hey, what’re you all doing? Get into the bomb shelter, this is getting bad!” We followed his orders.

I crouched motionlessly in the bomb shelter, but others were trembling with fear. After a short time, people from the factory came and said to us, “Things are really bad in Hiroshima. We can’t work anymore, so go home.” I left the factory with five or six friends.

As we were trying return to the city from Funairi-saiwaicho, a group of about about 50 people silently filed toward us on foot. There were women and men with dreadful expressions, with swollen faces and lips and their arms raised in front of them. Many of them were covered in blood and had torn clothes, and they walked toward us like spectres without saying a word.

As we passed these people, one of them said to us, “You can’t go that way, the houses are all burning,” so we retraced our steps to the factory. We decided to return via West Hiroshima Station in order to avoid going through the center of the city, and we set out from the factory again.

It started raining lightly around the time we arrived at West Hiroshima Station. When I stretched out my hand, the rain was black. At the time I didn’t know the rain was radioactive and dangerous, I only thought, “I wonder why black rain is falling? It’s so strange…”

I decided to try heading for where my aunt lived in Furue, close to West Hiroshima, so I put on my air raid defense hood and got drenched as I walked through the falling rain. When I arrived at my aunt’s house, I saw the glass had been blown out of the windows and the tatami had come off the floor; the house was in total disarray. After helping clean and finally clearing enough space to be able to sit down, my aunt brewed us some tea.

At that time, my aunt said, “It seems like a bomb fell right next to us,” and I replied, “Really? But I’ve come from the factory, and it seemed like a huge bomb fell there too. I don’t think this’s the only place that was damaged.” I couldn’t help becoming worried about my home in Ushita, so I said goodbye to my aunt and went back toward West Hiroshima Station.

I walked along the train tracks until Yokogawa and from there crossed Misasa Bridge into Hakushima. I could see then that Hakushima had burned completely — there was nothing left. “Bombs must have been dropped all over Hiroshima. Aah, this is horrible; Ushita must be in bad shape too,” I thought as I hurried toward Kōhei Bridge. When I got there, there were many military engineers burned pitch black, dying. Military engineers are soldiers who work as carpenters or make various things. The burned engineers were saying, “Help me, help me,” and “Please, water.” But I had heard not to give burn victims water, so I apologized to the engineers, saying, “I don’t have any water, so please be patient,” and crossed the bridge.

When I looked at Ushita from the riverbank, I saw that everything from Kōhei Bridge to the temple had burned completely. I could see that the main hall of the temple was destroyed, and I ran there with alarm.

I made it to the temple and called, “Father, mother!” My parents greeted me joyfully — “Oh, you’re home! I’m so glad, I’m so glad” — even though my dad’s head was bandaged and my mom’s arm was injured.

Although only the tilted framework was left, some of the temple hadn’t burned. When fire from the house next door caught onto the main hall, a soldier climbed onto the roof by himself and was able to put out the blaze by pouring buckets of water, brought to him by the neighborhood people, onto the fire from above.

The fire didn’t only come from the house next to ours; various places in the neighborhood were ablaze. When fire from the house on the outward side of the ginkgo drew near, the tree prevented the fire from spreading and saved the main hall from burning. When I returned to the temple around noon, the ginkgo’s leaves had all been blown away, and a large branch had broken off. Although the ginkgo was still smoking in about three places, fortunately it managed to endure.

We waited a little longer, but my younger brother Junji, a middle school first year, didn’t come home. Mom and I went out to go search for him. We crossed Kanda Bridge, and when we came to Hakushima’s streetcar line, around what is now the Hiroshima Prefectural Art Museum, a number of middle school boys and girls had thrown themselves down in a long line by the tracks. Everyone was burned, and their clothes were tattered. I tried to check if any of the boys were my little brother, but they were already at death’s door. Some said, “Please, water,” “water.” “I don’t have any, so please, hold on a little longer,” I was saying to them when suddenly I remembered that my brother wouldn’t be here because he had been working on building removal in Koamichō; mom and I walked on.

I learned later that when the atomic bomb was dropped, my little brother was in Koamichō at morning assembly before beginning work. Many of his friends died instantly, but thankfully my little brother was saved. However, his whole body was burned. He had been wearing a hat, and the heat from the bomb seared off his hair right along the hat’s edge and burned his face. He must have been wearing a short-sleeved shirt, because his arms were also tattered with burns.

Like me, it seems my little brother tried returning home through West Hiroshima; on his way, a soldier put oil on his burns, and he walked this way and that until he somehow managed to make it to the riverbank by Kōhei Bridge. He begged a woman for water. When she asked him, “Where’re you from, young man?” and he answered, “I live at Ushita-honmachi’s temple,” the woman said, “You’re from Anrakuji? In that case, please rest here. The area toward the temple is burning right now — you can’t go home that way.”

However, my little brother said, “My sister is married and living in Nagatsuka; I’ll go there,” but the woman replied, “You’re in no condition to go. I’ll tell the temple you’re here when I can; please just lie down.” So my brother slept there. If he had tried to go to Nagatsuka, I imagine he would have collapsed somewhere and we would never have found him.

In the evening the woman passed her message on to the temple, and I went to go get my brother, carrying a stretcher.

When I was told, “This is your brother,” I tried to check his face, but it had become so severely swollen that however hard I looked I couldn’t tell it was him. The name tag attached to his torn clothes was also burned and illegible.

But when I saw the design on the metal fittings of his belt, I thought, “Ah, it’s definitely him.” After I called his name and he replied “Mmhm,” I finally knew it was my little brother. As we carried him back to the temple on the stretcher, my brother spoke a little, but he couldn’t open his mouth, and his breathing was so faint that talking seemed really painful for him. My mother told him not to try to speak too much, so I wasn’t able to hear anything else that had happened to him.

Around August 10, my brother’s consciousness became hazy, and I heard him say, “Aah, I’m so tired! How many more meters?” I unthinkingly replied, “100 more,” but then felt guilty. I shouldn’t have said that, I thought. My little brother asked again, “How many more meters?” and this time when I answered, “Just one more,” he let out a sigh of relief. I believe my little brother had tried to come home with all his might, walking as if he was dragging his burned body home. I can’t help but cry when I think of it. My brother passed away on August 12.

Many, many people died from the atomic bomb. Many waded into rivers because they were thirsty and died there. Even in Kyōbashi River, people died with their arms raised and legs extended, looking like the kanji for “big”; their bodies floated and splashed. Those people were dragged out of the water and cremated near the bridge.

There were so many dead that there weren’t enough people to help with cremation, so we could smell the bodies rotting. I remember the stench of the dead pervaded Hiroshima until December of that year.

We didn’t learn until much later that the horrible bomb dropped on us was radioactive. After a little while, some of my friends’ hair would fall out if it was pulled on, and before long they passed away. I also had friends whose skin became spotted — we spoke, “What’s wrong?” “I don’t know why the spots appeared” — and those friends died too. Kids who said “I can’t stop my nosebleed” also died. Many people died like this as a result of the atomic bomb.

The children hung onto Toyooka-san’s every word. He spoke to them quietly and gently.

Have you all been to the Peace Memorial Museum? To tell the truth, I haven’t even gone once. It really scares me. I’m scared to revisit what I saw as I returned home from the factory, the figures of the wounded and the dead. But I hope people, like you, who don’t know about or haven’t experienced it go see the horrors of war and the atomic bomb. I want the world to never experience war again. I’m sure you sometimes have fights with your friends, but I hope you quickly make up afterward. I hope you all build friendships based on mutual consideration, never forgetting the value of peace.

Toyooka-san looked at the children one by one and, after a pause, continued speaking.

Returning to the story of the ginkgo, the tree never returned to how it was before being scarred by the atomic bomb. However, the large, broken branches left alone in the garden put out sprouts the next spring. When I saw that sprouts could come out of a broken branch without roots, I thought that ginkgo must be trees with plenty of moisture. Thanks to that moisture, the tree didn’t suffer quite as much from the bombing.

Seeing the ginkgo sprout like that, I thought, “People say nothing will grow in Hiroshima for 75 years, but that’s not true!” After a number of years, the ginkgo at last returned to full leaf. At first the tree put out strangely shaped leaves, but now they have become as splendid as ever.

The trunk still has parts that were burned and withered, but arborist Horiguchi-san said to me, “This tree is full of life.”

All the leaves are green right now, but come December they will turn completely yellow and sprinkle to the ground like falling snow. Everyone, once the beautiful yellow leaves drop, please come and take home as many as you like. Once the leaves have fallen entirely, only the withered-looking branches remain. Although it looks desolate, the tree is still living, and in April new shoots will bud again. Ginkgo are also magnificent when they’re in new leaf. This one is wonderful to look at throughout the year.

・ ・ ・

The students had listened to Toyooka-san’s story seriously. I’m sure thinking about what occurred in their own neighborhood due to the war and atomic bombing was a valuable experience for them. Going out into the garden, the children gathered under the ginkgo and made a circle around the trunk. If five kids stretched out their arms and joined hands, they could just manage to encircle the whole tree. Others competed to see who could jump high enough to touch the ginkgo’s branches. Children seem to have an endless capacity for inventing games.

I spoke with Toyooka-san after the children had gone home, as we gazed at the tree. Toyooka-san said that in his childhood, the ginkgo had even more leaves, and he would play by hiding in mountainous piles of trimmings. Thinking again of the elementary school students who had been here just a little while ago, I tried to imagine Toyooka-san playing under this ginkgo with his little brother.

Toyooka-san has seen 50 years pass since the war’s end, but he only began taking advantage of any request to speak about his experiences not long ago. Until recently, the story of his brother had been too painful, and he couldn’t speak of it. Toyooka-san was exposed to the black rain and radiation while he searched for his little brother. He was bedridden with a fever for two or three days after being exposed to the bomb, and, aside from getting cataracts much later in life, Toyooka-san has not had any other symptoms thought to be the effect of radiation. However, a year ago he was found to have cancer, which Toyooka-san feels is an effect of the atomic bomb. “I’ve gotten weaker, and I wondered if I would be able to speak to the children today, so I’m glad I could in the end,” he said quietly.

I hope Toyooka-san is able to continue his long, resilient life, like Anrakuji’s ginkgo, and in health keep speaking to children. The desire to cherish peace will continue to grow in the hearts of the kids who come to Anrakuji to listen to his story and play under the ginkgo.

* * *

「安楽時の前住職・登世岡浩治さんの話」、石田優子の『広島の木に会いにいく』、 125-141ページ

Meeting Hiroshima’s Trees is published by Kaisei-sha (偕成社). Excerpts are posted with the permission of the author. Translations are my own, as an individual.

Links to previous Hibakujumoku Translation posts: