On 6th August 2012, the 67th ceremony to mark the atom bombing of Hiroshima was attended by Ari Beser, the grandson of Jacob Beser, who was on board the Enola Gay when the bomb was dropped. Also present at the ceremony was Clifton Truman Daniel, the grandson of President Truman.Beser and Truman laid wreaths at the cenotaph in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, “to honor the dead, to not forget, and to make sure that we never let this happen again.”

In the last section of this news report, Ari Beser talks about the motive for his visit:

Ari Beser later agreed to answer some questions about his perspective as the grandson of one of the air crew, and in the light of his visit to Japan, where he met several a-bomb survivors.

1. Could you explain your connection to Hiroshima and Nagasaki through your grandfather? What memories do you have of him?

My grandfather Jacob Beser was a lieutenant and Radar countermeasures officer on both the Enola Gay and Bock’s Car. He was subsequently the only man who directly took part in both atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

I have very few memories of him as he passed away from bone cancer (related to radiation exposure) in 1992, when I was only four years old.

However what I lack in memory is supplemented by the immense library of records he left behind, including handwritten speeches and diaries, videotaped interviews, and talks, and copies of military records. He also wrote a detailed memoir about his experience in World War II and returning to Japan in 1985. So I have been able to listen to his perspective without actually speaking with him about it. However there is no way of knowing what he would have believed in the context of 2012, as he passed away 20 years ago.

2. When did you first become more deeply aware of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Nuclear weapons?

My answer to this question is also the answer to the next question.

3. What has led you to engage in efforts for peace and nuclear abolition?

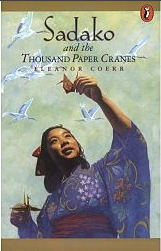

In middle school when I read the book Sadako and the 1000 Paper Cranes, I felt a sense of connection to her, like we knew each other, even though she was just a girl in a book.

That sense was realized in 2011 when I was introduced to her nephew, and we realized we wanted exactly the same things, though we came from opposite sides.

I should say that I came to Japan because of a coincidence. That coincidence is that my other grandfather on my mother’s side was a friend with a survivor who lived in Baltimore. I came to Japan in 2011 to understand her family’s perspective, but that visit turned into this whole project. I learned of a Japanese legend of the red string of fate, according to which everyone destined to meet has an invisible thread tied to that person.

I believe the people I met in Japan, who helped me gain a greater understanding and who have facilitated this movement were people I was always supposed to meet. I think we were supposed to get together to send a message to the world.

Meeting my grandfather’s friend at a young age was the very begining of my awareness of the Japanese perspective, and a huge reason for my interest in engaging in these talks. Fate seems to be pointing me in this direction. I am not able to talk about my grandfather’s friend’s story publicly as her family wants to remain private, but they understand how strange this “coincidence” is and permit me to explain my reasoning for starting this project, without talking about who exactly they are.

4. What were your strongest impressions of the time you spent in Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Were your experiences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki different in some way? How?

My strongest impression about Hiroshima and Nagasaki is that in these cities, peace is not an idea, it is not a concept, it is a way of life enacted. People don’t scoff at the idea here, like they do in the states for example. People live it, they breath it, they believe it, and thus have it. When I came to Japan I was nervous that people would be angry with me. I was surprised at how compassionate everyone was, and it gave me hope that if we can reconicile something that was what my grandfather called “the most bizarre and spectacular two events in the history of man’s inhumanity to man,” then anyone who is in unending conflict can have the same hope that they too might be able to be reconciled and live in peace.

5. What was it like for you to meet with A-bomb survivors?

In a word? Hard. Their stories are unimaginable, but they lived through it. I kept reminding myself there was no way I could feel bad, because I did not witness what they did.

The only thing I could do was listen, and realize just how disgusting nuclear weapons are. They are not just bombs, they alter DNA, they mutilate people and make people suffer well after they explode. No one should live through what they lived through, but the entire time I reminded myself that not many people have heard them directly tell their stories, and how crucial they are to the development of peace. I felt then as I feel today.

We cannot forget their stories, we have to remember them forever, and hopefully if we can preserve their stories, than we can make sure that there are never any stories like theirs told by anyone else.

6. You took part in the Youth Peace Forum at the YMCA, where the theme was “The Lessons We Have Learned.” What would you say were the lessons you yourself learned, or that were driven home more deeply, from your visit to Hiroshima and Nagasaki?

One thing that sticks out in my mind today, among everything else I mentioned above, was at that talk when Steven Leeper said,

“It would only take ten nuclear bombs to create something called nuclear frost. It wouldn’t be as encompassing as nuclear winter, as there wouldn’t be total blackout of the sun, but it would be enough to destroy the world’s agricultural system, and leave us in a survivalist state.”

Usually when you hear things about nuclear bombs, people understand what nuclear winter is, but they don’t think about nuclear frost. I never realized it could only take ten nuclear bombs to detonate to throw the world into a tailspin.

I learned also that I have a lot to learn. I think when people think they understand everything, it can either be a starting point for realizing they don’t understand anything, or they remain ignorant to the impossibilities of the world’s forces. I don’t think anyone could understand everything, they would have to be the creator of the universe to claim such a thing.

I think once we accept that we don’t understand anything, then we can begin to work together to create a world that makes sense for everyone.

I learned a lot about the Japanese perspective that does not get taught in the American education system, and I learned about the realities of war, and what it meant for the everyday Japanese person, and not just the soldier. Not everybody wanted the war, and governments have a duty to protect the world we live in, not turn our people against each other.

7. How do you imagine your life in the future? What passions and goals will you pursue?

I want to write a book about the experience I had with the Japanese survivors, and my grandfather’s experience of being on the crews, and how he came to the conclusions he did.

In the long term, I hope to spearhead an initiative that is still very premature, but will hopefully expand upon what Clifton Truman Daniel and I did in August 2012. I believe that we should digitally preserve the hibakusha’s stories by videotaping their accounts, and storing them in a place like the Truman Library. I am in the very early stages of beginning that effort, and nothing is confirmed as of today, but these are my desires for the future.

I hope that the work we create can be used to educate people and create a strong desire to rid the world of nuclear weapons. We live in free societies, nothing happens unless the majority wants it to happen.

My goal is to help create that majority, and find a way we can realistically get rid of the nuclear threats that disrupt world stability today.

I know how young and inexperienced I am, but what I do have is a will, and a passion to see this through to the end. Why wait for someone else to do it? I do not have to be alone in this endeavor and indeed I am not, but the more people that take up the initiative, the faster our collective goal will be realized.