Akio Nishikiori was eight at the time of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. After the war, he gained qualifications as an architect and set to work assisting in the reconstruction of Hiroshima – with the aim to rebuild it as a city of peace.

This interview was conducted in Japanese and has been translated so that Nishikiori-san’s story can be spread around the world, to encourage people to think more deeply about peace and the role of nuclear weapons in the world today. The interview was spoken and has been translated as is, so read it as if somebody was talking to you.

All photos provided courtesy of Akio Nishikiori.

Living through the bombing as a little boy

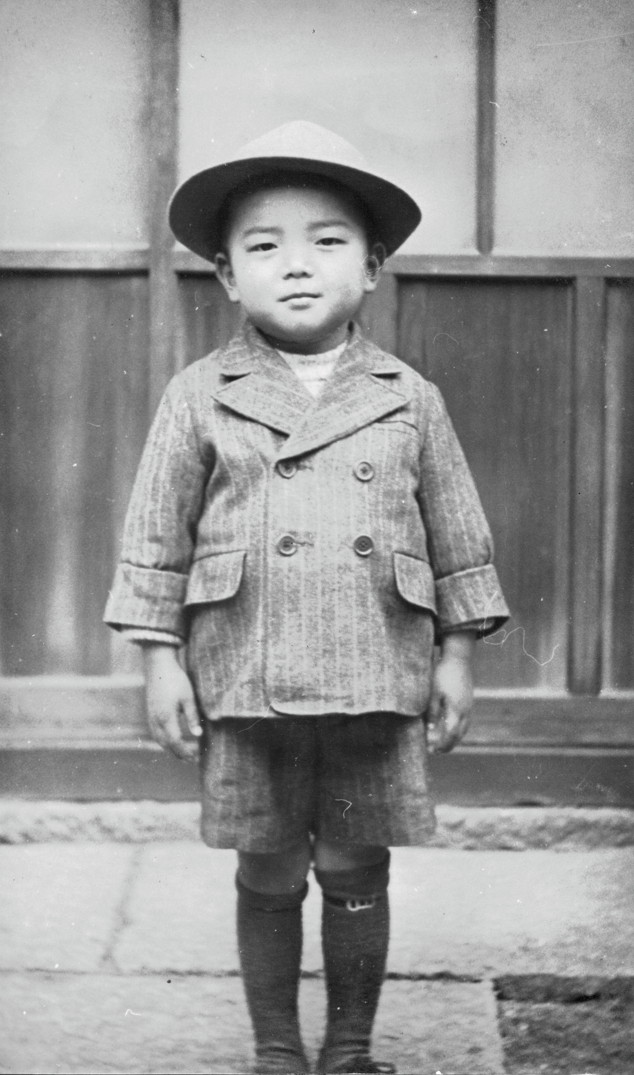

Akio Nishikiori, aged 6 (photo taken 1943)

This photo was taken two years before the bombing. You can see on my shirt, there’s extra stitching, so that no matter how big I got, they could just resize it and I could keep wearing it. Everybody wore clothes like that back then. I was six and a half years old at the time. Everybody thought I was a bright, naughty little boy. I couldn’t tell the difference between the word for soy sauce (shoyu) and the word for artillery (shoi), so when people were talking about artillery shells (shoidan), I thought people were making soy sauce bombs and got really confused. We had a servant called Moguro-san from Shimane prefecture and he was very polite, as he was our servant, he wouldn’t ever ask for a second helping of dinner, but would accept, saying “If I’m allowed to…” if you asked him. I was little, so I copied his way of speaking without thinking and made everyone laugh. It was a really peaceful time, until the sixth of August 1945.

My family

At the time, I was living in a family of seven, myself (in my second year of primary school), my mum, my grandma, my great-grandma, my two older sisters (one who was in her fifth year of primary school, and the eldest one who was in her second year of middle school), and my three year-old brother. Dad was living apart in Shobara at the time. My dad was a military man, he was the head of the unit at Shobara and was mostly leading domestic support efforts for the army’s operations. Dad was a staunch militarist, and when my mum asked him to move us to safety in the countryside, he told her that my sisters’ participation in building demolition works was their way of participating in the war, and that *evacuating would be the same thing as running away, and that cowardice is not something I can forgive.” He moved himself to Shobara, which was in the countryside, and left us behind in Hiroshima City for a period of the war.

There were so few other young children like me left in the city at the time, most of them had been sent out to the countryside, I had no real lessons at school since there were so few students. Like my father, my older sister was also very against moving to the countryside, she was going to school and working for the country in building demolition, if she got sent to the countryside then she wouldn’t have any work to do. She was a little militarist, everybody was back then, that’s how education worked; and so she was completely opposed to the thought of being useless to the war effort. My mum was very persistent, and eventually forced my dad to evacuate us to Shobara at the end of July, but we were still in Hiroshima for a while after that as we had to find a good school for my sister.

The Bombing

Air raid sirens were blaring all night on August fifth, so nobody in the city had any rest during the night. When morning came around, everyone was exhausted, as they had been running into the shelters and then going back home once the all clear was given multiple times through the night.

The weather on the morning of the 6th of August was perfect, a bright blue sky with not a cloud in sight, the perfect weather gave people a bit of a boost after such a tiring night, it felt freeing for the sky to be so clear. My sister’s school in Shobara had been decided too, so we had solved our remaining problems and felt free in that way too. Nevertheless, we were still in the city and my sister wanted to work until the very last moment, so she headed out to her assigned workplace.

When the bomb went off, the other six of us were at home in Hakushima. I was watching my mum do the laundry with a washboard and trough. My little brother was playing outside, but since it was dangerous, my grandma had just brought him back inside the house. My other older sister and great-grandma were packing our clothes into baskets in the lounge room.

Suddenly there was an unsettling cracking noise outside, and there was an insane light, as if you had lit thousands of sticks of magnesium on fire at the same time. My mum screamed out, “A bomb’s fallen in our garden!”. At the time, we were trained to find and put out fires as soon as bombs were dropped at school, so I raced to see it. I ran down the hall and just as I was passing the stairs, there was an almighty roaring boom outside, I saw the clothes in the lounge get lifted up, but then lost consciousness as I got thrown across the house by the shock wave. Because I had so much time to get through the house, it felt like eternity had passed in a few seconds, it felt so long; but now when I look back and think what happened to Hiroshima within those few seconds, I freeze and can’t move. I really think it was the most horrific time in the world.

My sister and great-grandma were thrown out of the lounge, my sister was tossed into the hall and into the wall, my great-grandma was tossed out of the house altogether and landed on a flower bed. Grandma was a strong, sturdy woman who always very good during evacuation practice, and she gathered us altogether, my sister, brother, great-grandma and I, in front of the bomb shelter we had on the property. Mum was moaning awfully, she was completely pinned underneath the rubble of our house, but my grandma managed to get her out.

The hellish gardens – the overwhelming screams of not just people, but horses

Our designated evacuation point was Chojuen, a botanic garden 100 metres up the road from our house. We evacuated there, but the walk there is a horrific, nightmare-like memory to me, filled with smoke, dust and blood. I saw babies thrown by the wave that were hanging from trees, heard screams for help from every house between ours and Chojuen, All of our family and everyone else around was unrecognisable, mum especially, the whole way she had blood pouring down her face. She collapsed on the way, grandma slapped her to wake her up, but she cried that she was too far gone and told us to leave her behind. We couldn’t so we supported her the rest of the way and somehow got to Chojuen. Everybody around tried to push through their grievous, in many cases mortal injuries, to try and stop the flames from swallowing up what was left of the town.

The thing that left the biggest impression on my memory was the terrible screams of horses who were being swallowed up by the flames. At the time, fuel was scarce and cars rare, so horses were the main method used for transportation and moving cargo. They were everywhere since people relied on them so much. Of course, they were all tied up, and so when the bomb was dropped, those who weren’t just vaporised, were swallowed in flames. They let out terrible cries as they burnt, I didn’t know horses could make that sort of noise, the cries still ring in my ears today.

We had to wait in Chojuen until the truck my dad had dispatched for us to come and pick us up, so we spent the night of the bombing, as well as the next day and night sprawled out on the grass. Mum was completely incapacitated, so grandma sprang into action, running back to our shelter to bring food supplies and going out searching for my eldest sister who still hadn’t come back. Even as night fell, she still hadn’t come back. Most people of course didn’t have any food, so there were many people who ate ‘bomb fried chicken’; pigeons who had been charred by the explosion and fallen to the ground. After people learnt that it was a nuclear bomb, they started referring to it as ‘nuclear fried chicken’ instead.

Countless people died in the park that night. Countless people spent the whole night helping others however they could. Amongst all this, two sisters who were about the same age as me (likely in their third or fourth year of primary school) started singing. They sounded beautiful, but there was an overwhelming sadness as they sang of returning to a faraway place; they died during the night. During that hellish day, they had likely lost all of their parents and all of their family, it was as if they were chasing after them. Those nights in that park were a truly hellish scene of human tragedy.

Searching for my lost eldest sister

The day after, the truck came to take us to Shobara. Grandma had been searching through piles of bodies for my eldest sister, but hadn’t yet found her. Mum refused to go until we found her, but mum had massive injuries and was barely hanging on to life as it was, so with a painful reluctance the decision was made to go without my eldest sister. We spent the whole night driving, and eventually got to Shobara on the morning of August 8th.

Dad moved extremely quickly once we got there, he had mum and grandma given treatment for their injuries. The next day we left them in Shobara for treatment as dad loaded up a truck with us kids, doctors and nurses, and headed back into the hellish remains of the city to treat the injured and look for my sister. The city was so perfectly flattened that from the former city centre we could see the islands floating in the ocean, dozens of kilometres away. When we got back to the remains of our neighbourhood, I found our German Shepherd unharmed digging around the rubble, then in the pond in our backyard, the Koi were still fine, swimming around.

As we drove around the neighbourhood, I saw a boy, the same age (8), that used to bully me. He lived alone with his dad, but his dad had obviously perished in the aftermath of the bombing, and he had scratched out a shallow grave with a stick, and was cremating his own dad. It was one of the saddest things you could imagine. The bombing happened in the middle summer, so it was hot and humid, and if bodies weren’t burnt right away they would have rotted rapidly and disease and pests would have been even worse; most survivors in the aftermath were forced to cremate their lost family members.

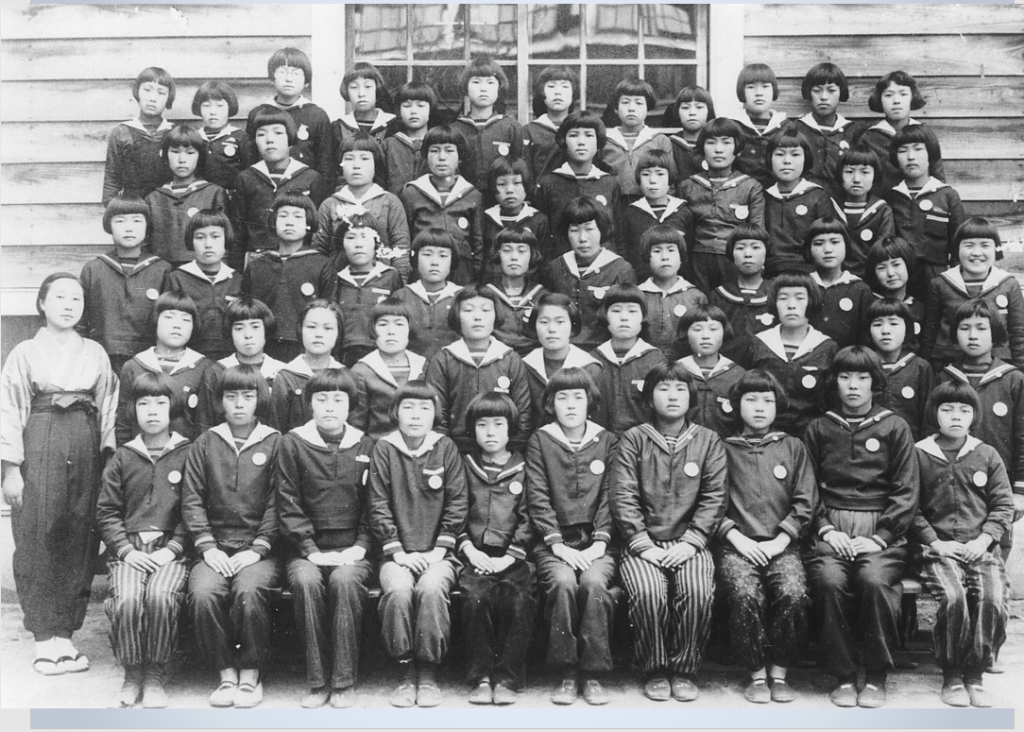

Nishikiori-san’s eldest sister’s class photo (she is fourth from the right in the second row from the front; only three people in this photo survived)

We stuck a big poster on the remains of our house, asking anybody that heard anything of my eldest sister to contact us in Shobara. We looked the rest of the day, but couldn’t find her anywhere. A week later, on the 13th, there was a call saying that my sister had been located, terribly wounded, but alive, at the Mazda factory. A woman who was searching for her own child had gone to the factory, my sister had told her our address in Hakushima, and the woman had walked all the way across the city to our house, seen the poster and called us. We couldn’t thank her enough, and she told us “looking for our children is something we must do together.” I still don’t know whether she found her own child, I still think about it to this day.

Dad loaded up a truck with doctors and nurses and headed for the Mazda factory, he returned that afternoon with her in tow. The right side of her body was horrifically burnt, it was mysterious, the inside of her mouth was burnt and was filled with blisters. She was leading her workgroup, so no doubt she had turned to directly face the hypocentre when she heard the first sound. Her face was practically gone, she was so badly burnt. The futon she was brought on had been moistened with tea so that it could provide some relief from the heat.

Her skin was both covered in, and filled with maggots who were burrowing there way into her. The nurses were removing them with tweezers, but there were far too many so we all joined in, using chopsticks to remove them as quickly as possible. She must have been in indescribable pain, but she held her screams back and gave my father a detailed report of what had happened to her during the bombing, how she had tried to go home, but was cut off by the sea of flames; the name of her friend that had fled east; the name of her friend who had thrown themselves in the river, dying of thirst; and how she ended up at the factory.

She spoke whenever she could for the two days after we brought her to Shobara. but on the 15th, moments after the Emperor’s Broadcast announcing Japan’s surrender, she suddenly fell quiet, muttered thanks to each one of our family, and passed away. Somehow, though she was burnt, she had a peaceful look on her face as she passed.

Nishikiori-san’s eldest sister.

The week she spent in a dirty corner of the factory, in dreadful pain, longing to be with family but with no guarantee that she’d be found, I can’t imagine how painful that must have been for her. I’ve had to have countless surgeries throughout my life, but each time I recall her and the pain becomes bearable, nothing I could go through would ever compare to what she did.

Hiroshima’s reconstruction – becoming an architect

After the bomb was dropped, it was said that nothing, no plants nor animals would be able to grow or live in Hiroshima for 70 years or more. Contrary to this, Hiroshima rebuilt rapidly. Within three days of the devastating atomic bombing, Hiroshima’s trams were running again.

Hiroshima is an incredibly resilient city.

The reconstruction of Hiroshima was based on four important principles:

- A spirit of making a strong stand against the cities fate in the bombing.

- A dream of building a peaceful future.

- A thorough plan to make a stronger city

- A city in which you can see the sky, so the buildings are kept low

- Sacrificing immediate comfort for the benefit of the long-term prosperity of the city.

This was built into the construction laws of Hiroshima following the war.

The first priority – building houses

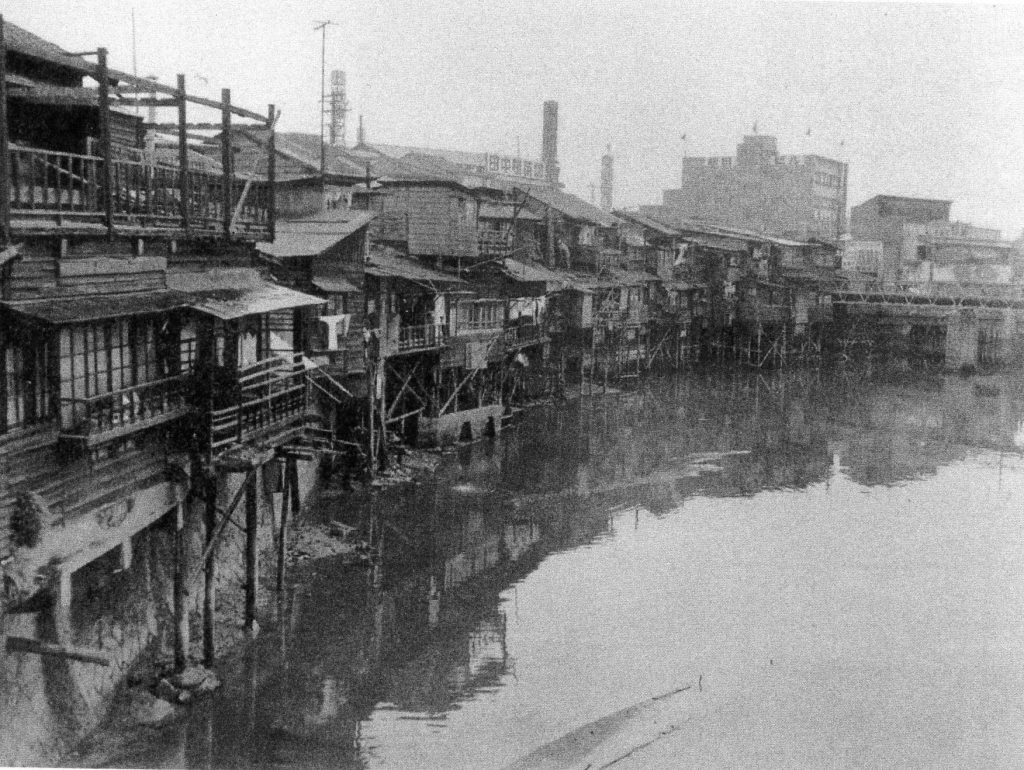

Genbaku slums next to the river. The houses were so tightly packed and quickly built, that it was possible to move between houses and they often ended up like mazes inside.

Of course, given the city had been completely wiped out, the first priority for the government and the people of Hiroshima, was to build houses so people had places to live. Most people quickly threw together scrappy huts, and with very little oversight from the government. The areas filled with these houses and the bombing survivors who lived in them, were called ‘genbaku slums’ (atomic bombing slums).

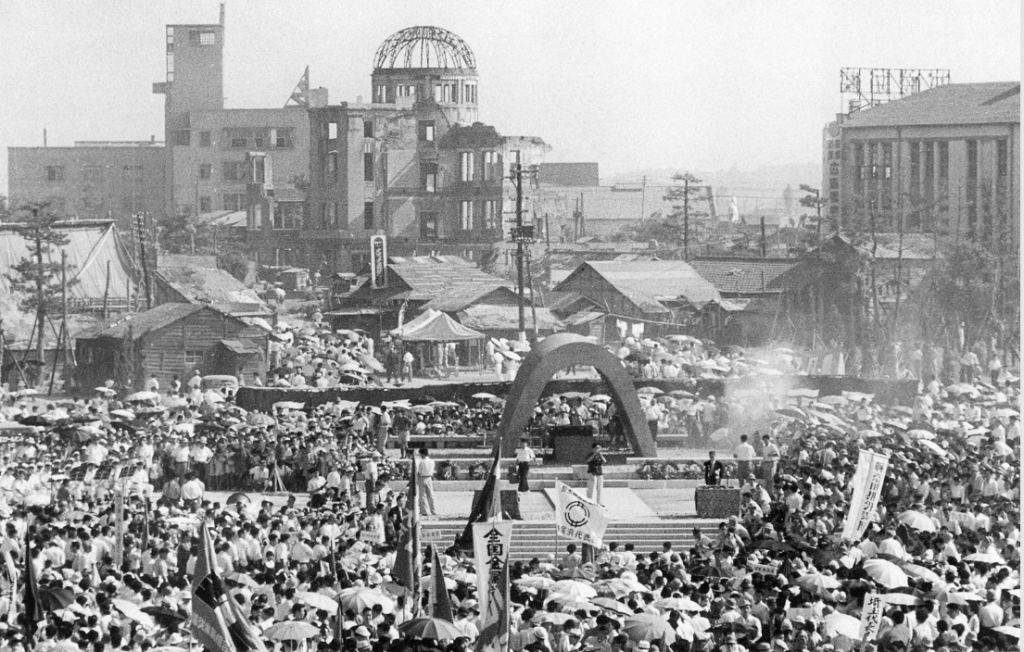

Huts thrown together in the area around the present Peace Park; the Genbaku (Atomic Bomb) Dome is visible in the background. (1946)

The entire area around what is now the peace park was the downtown heart of Hiroshima at the time, and it was completely destroyed by the bombing, so people who were gathering in what used to be downtown built houses there too.

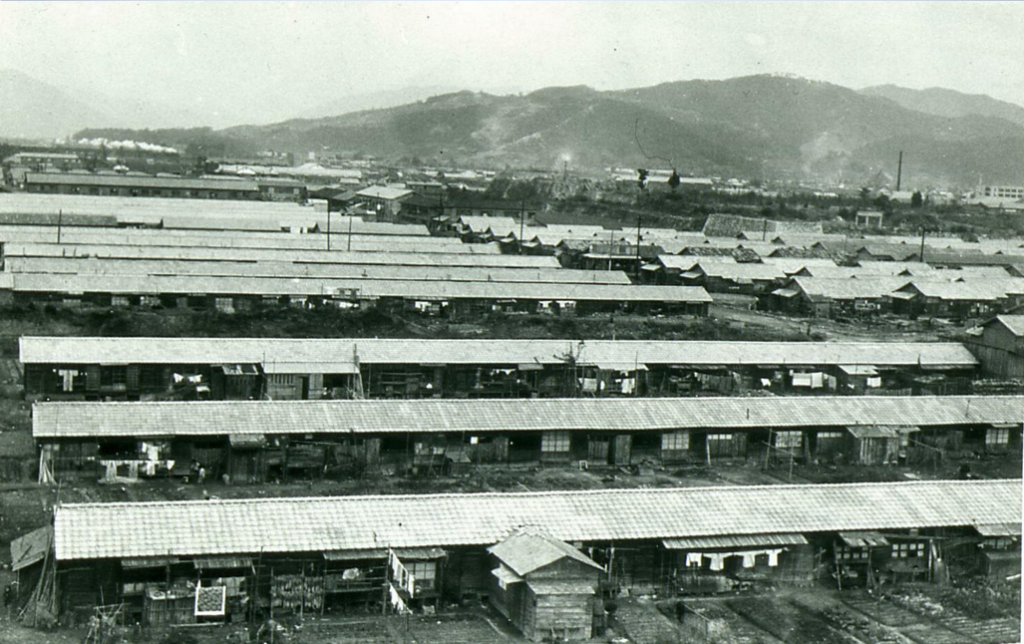

Government built housing, a few years after the war (~1947)

The government built houses were more orderly, but also were far insufficient compared to the demand at the time. At the start of World War II, Hiroshima’s population was a touch over 360,000, in 1942 it rose to 420,000, and at the time of the bombing there were roughly 375,000 people in the city; half of whom were killed by the end of 1945, when the population had fallen to 137,000. It returned to pre-war levels in 1955, and today is home to 1,200,000 people, the tenth largest city in Japan.

Reviving the city’s heart

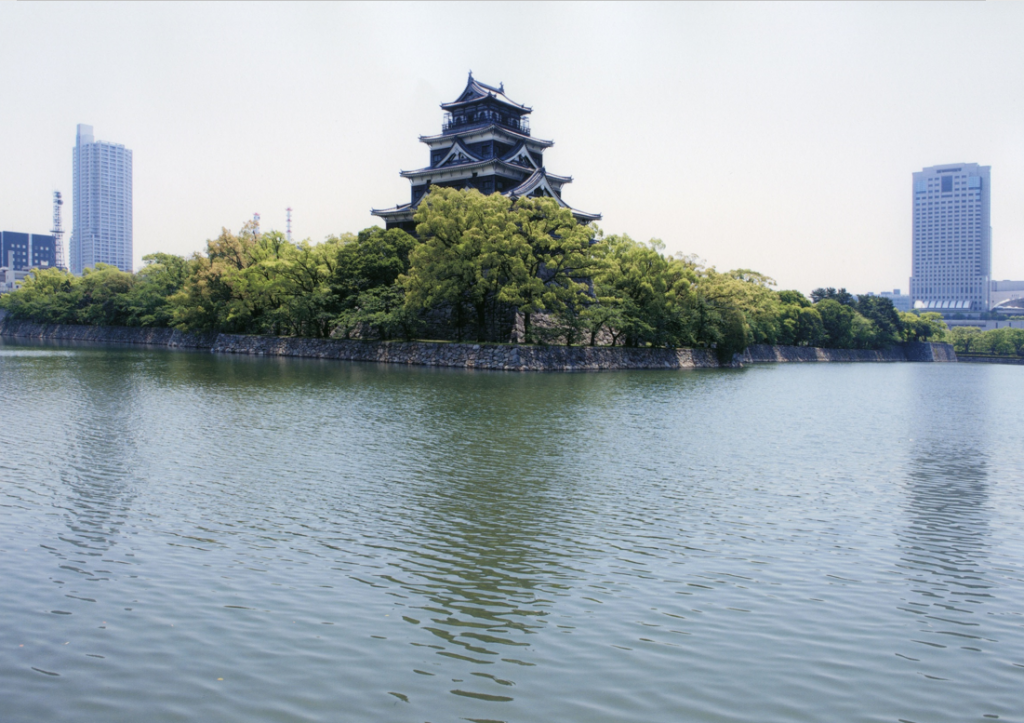

In addition to housing, to revive the people’s spirit, those symbols of Hiroshima, the castle, the shopping streets and such, of course had to be brought back as well.

The remains of Hiroshima Castle and its desolate moat following the bombing, October 1945.

Hiroshima Castle today.

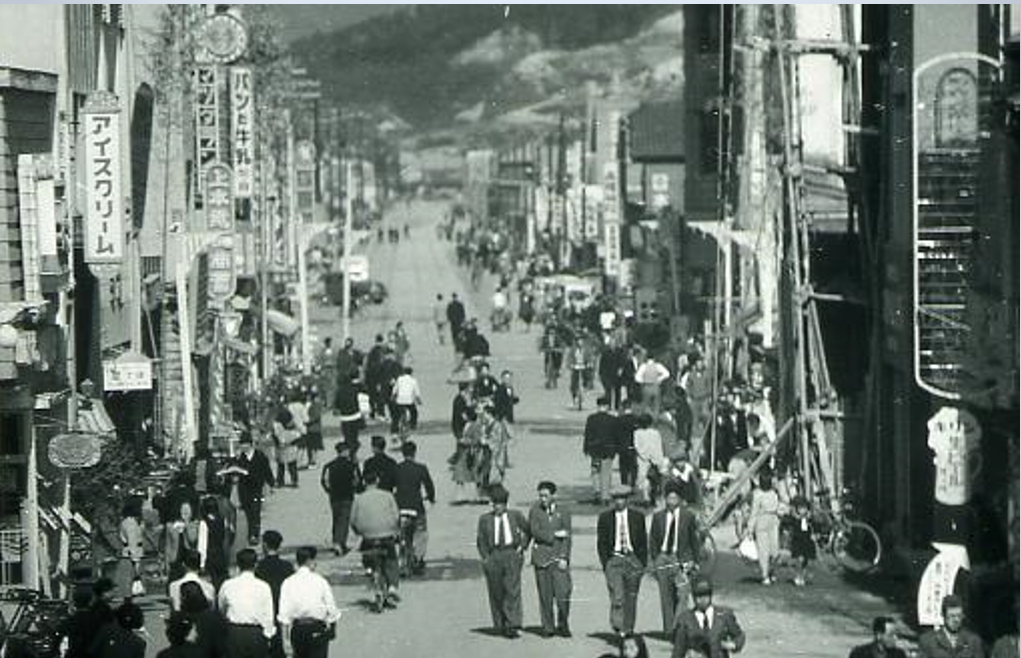

The shopping and commercial districts of Hiroshima, such as Hondori and Hatchobori, sprung back to life at great speed after the war. It took many years for the government to enact regulations and plans to develop them into something as grand as their pre-war form, so they came back as collectives of smaller shops, each specialising in their own thing. Eventually, I got the opportunity to build the arcade for one of Hiroshima’s premier shopping districts, Ginzagai in Hondori.

Hiroshima in ruins, late 1945.

The same area today.

One of Hiroshima’s main shopping streets a few years after the war ended (~1948)

The more developed shopping street today; Hiroshima’s famous Kinzagai arcade, designed and built by Nishikiori-san.

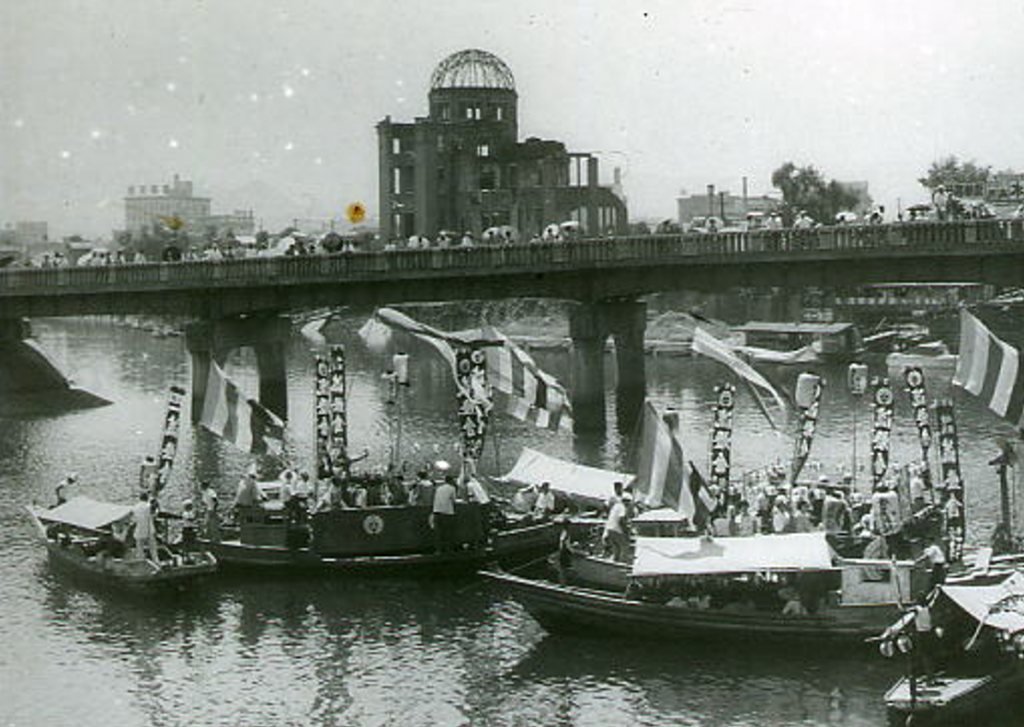

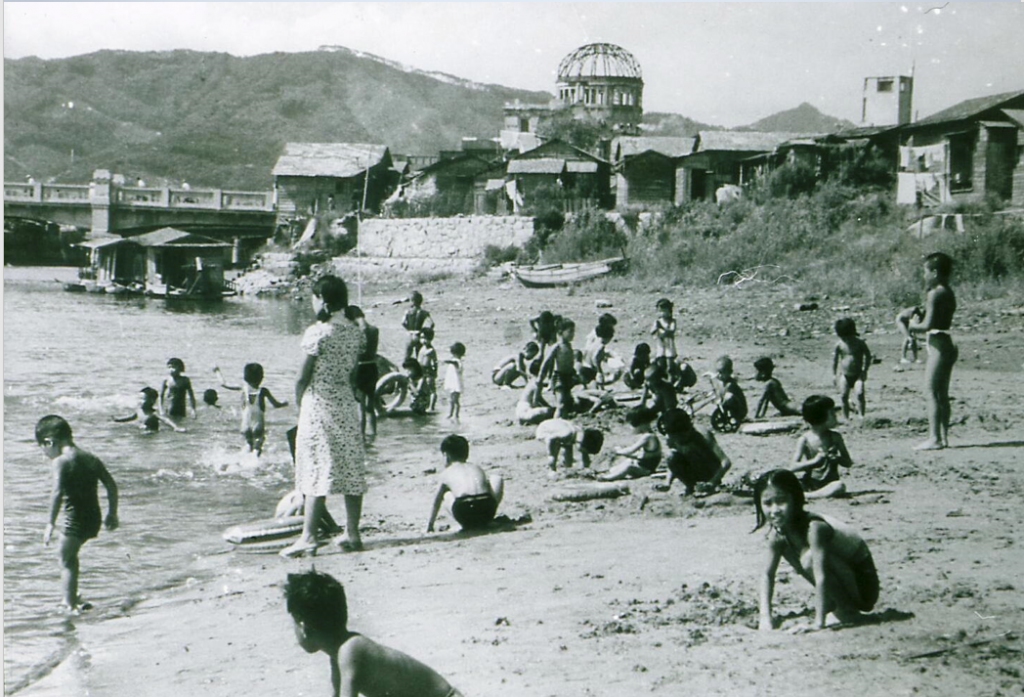

Although the city of Hiroshima has become more developed and more modern, it has for a long time placed an importance on greenery, and as such it has more open green spaces than any other city in Japan. That’s something to be proud of, but there are two things I strongly dislike. One, the recent moves to develop green areas which had long been protected, into such ridiculous frivolous things as stadiums; when we already have plenty of those. Two, the way in which the riverside area has been cutoff from people, so people can’t really enjoy the river anymore. Even in the years straight after the war, it gave people comfort, but now it’s so artificial; I wish they would put more importance on the connection between people and nature.

Boats on the river during a festival.

Children and families playing by the river (~1948)

The riverside today.

The extent of the damage

Following the bombing, Hiroshima was practically wiped from the Earth, yet it grew back, bigger and stronger than ever. Today the city is a symbol of peace.

Downtown Hiroshima a couple of weeks after the bombing; practically all buildings were wiped out.

The same area today.

Another perspective of a blackened, flattened downtown Hiroshima after the bombing

The area today.

Hiroshima’s mission into the future – A city of peace

To ensure that the horrors of atomic weapons, and of war at large, are never forgotten, the cenotaph housing the names of all the known victims of the bomb was built in 1952, the Peace Park in 1954, and the Peace Memorial Museum was constructed in 1955. Following this, the Children’s Peace Monument was built in memory of Sadako Sasaki in 1958, and the Eternal Peace Flame was lit in 1964.

The area around the Atomic Bomb Dome, November 1945.

The opening ceremony of the memorial cenotaph in 1952.

The Peace Memorial Museum under construction in 1953. Graves surround the construction site.

To ensure that these horrors are never again repeated, we must remember not only the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but war in general. Japan was not just a victim, Japan was an aggressor during the war and that fact must be faced for Hiroshima and Nagasaki’s true mission, the achievement of a world truly at peace, to be fulfilled. We Hiroshima citizens must always be awake to the pursuit of genuine and lasting peace.

English translation by Liam Walsh.

One Reply to “Rebuilding Hiroshima – Akio Nishikiori: Atomic Bombing Survivor, Architect”