In a nation called miraculous for its transformation from burned-out desolation to economic powerhouse, the scars of war were quickly hidden by dazzling recovery. Children who suffered physical and mental trauma in the American bombing of Japan during World War II hid their pain and lived quietly, trying not to trouble others. Now, through photojournalist Kazuma Obara’s work, some are finally sharing their “silent histories.”

Originally a self-published — in fact, handmade, with only 45 copies produced — photobook, the photography exhibition Silent Histories was held in Hiroshima at the gallery Intersection611 from 21 April to 3 May.

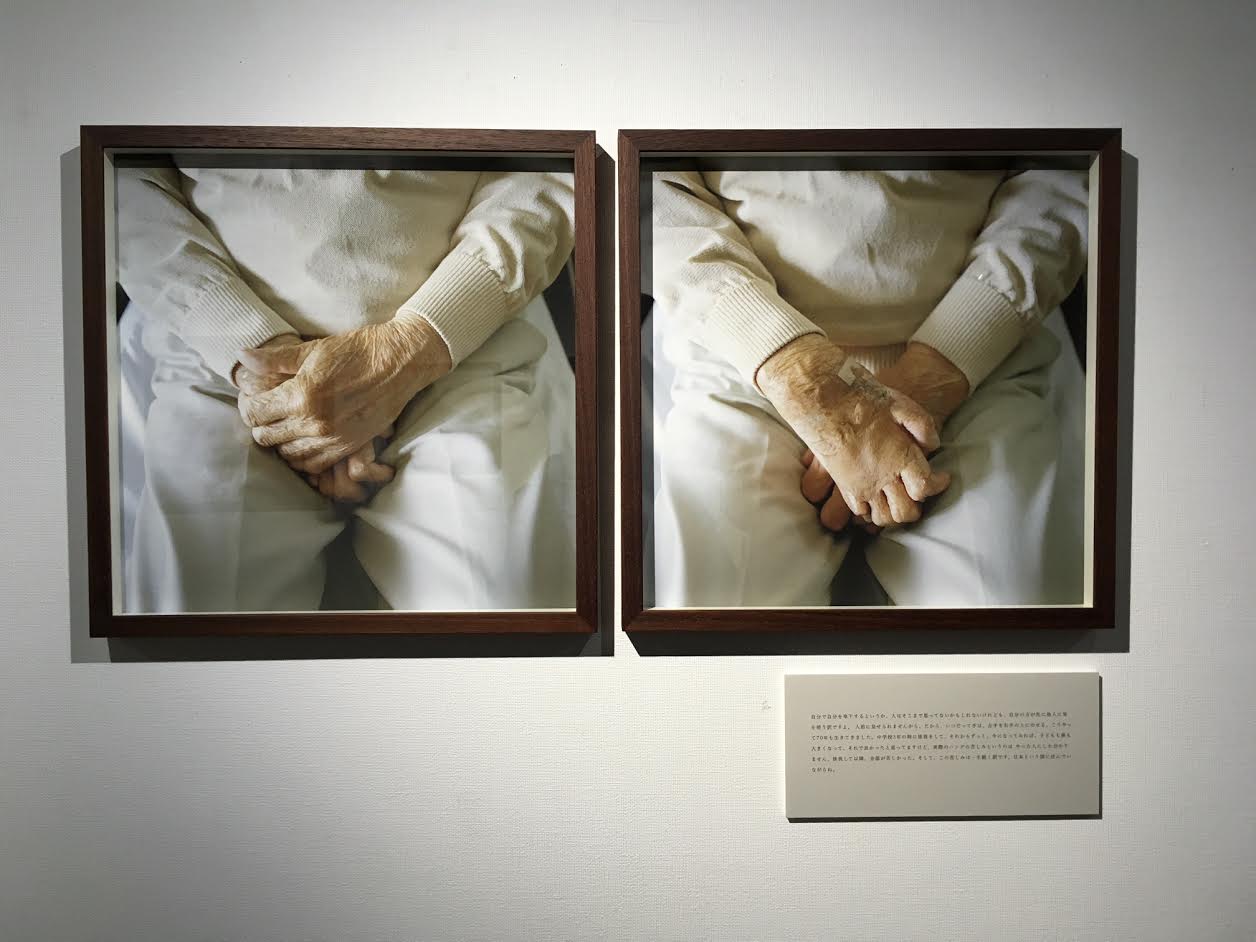

The exhibition focuses on the personal stories of a few individuals who were children during WWII and experienced the bombing of Osaka. They suffered permanent injuries or saw family members killed in an instant. Along with portraits of the victims, the exhibit also utilizes aerial photographs of the bombing taken by the U.S. Army and shots of present-day Osaka, taken 70 years to the day after the bombing. Although some 400 Japanese cities were bombed during WWII, killing 330,000 people and injuring another 100,000, focusing on the histories of individuals personalizes the mass bombings that happened during the war. As years passed, reminders of war in Japan faded, although victims’ pain often did not. Now in their 70s and 80s, some victims are only just beginning to share their stories. Obara wants convey the experiences of war young people, to catalyze them to imagine the feelings of and sympathize with the victims.

At an artist talk event at the exhibit, Obara said he was inspired to create Silent Histories after seeing how victims altered photos of themselves. In particular, one woman, who lost a leg when Osaka was bombed, blacked out the lower half of her body with a pen in a class photograph. Obara said that more than seeing people’s actual scars, he was struck by how they hid them. His reaction made him wonder about the extent to which current generations can feel the pain of those victimized in WWII, and he also wanted to explore why victims felt pressured to hide their scars. Often, the answer to the latter was that the victims faced discrimination for their disabilities.

Below many of the photographs, Obara included quotes from their subjects. They explained what happened to them during the war and how their experiences impact their daily life even now. For example, one of the woman who had lost a leg was quoted saying that the first thing she does every morning is attach her prosthetic leg and that she can’t even reach the bathroom without it. She said that pain is part of her daily life and that she wouldn’t wish this suffering on anyone.

Although Silent Histories focuses on Osaka, the exhibit has particular relevance in Hiroshima, where large numbers of mobilized children working in the city were killed, lost family, or were left with mental and physical scars by the atomic bombing.

Obara also spoke about his work prior Silent Histories. He was the first photojournalist to photograph inside the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Although publishing his work, which also included portraits of and interviews with power plant cleanup workers and photos of the surrounding affected area, proved difficult in Japan, the material was published as Reset Beyond Fukushima with the Swiss Lars Müller Publishers. Obara mentioned that he was interested in the theme of whether a child feels free to say they’re related to a power plant worker, but he stopped the project after realizing the family portraits he wanted to shoot would out workers’ children.

For the past few years, Obara has been working on a project about the Chernobyl nuclear power plant and those affected by the disaster there; he is also interested in how Chernobyl is portrayed in popular media. His series Exposure, which focuses on the story of Mariya, a young woman who was exposed to radiation from Chernobyl while in the womb and who suffered health problems ever since, won first prize in the 2016 World Press Photo contest.